Bond risks

Photo by Viktor Forgacs on Unsplash.

Now that interest rates are back at historically normal levels1, bonds look a lot more interesting. Bonds let you grow your wealth and produce income while taking on modest levels of risk.

“Modest levels of risk” is not the same as risk-free, of course. So let's talk about some of the risks of buying and owning bonds.

I'm going to focus on individual bonds here instead of bond funds. Bond funds are fine. We own shares of a couple (namely VTEB and FBND), but they're a different investment vehicle with a slightly different set of risks. I'll explain more in a future post.

Default Risk or Credit Risk

Perhaps the most obvious risk is the risk of default. A bond is a type of loan. As with any loan, there's a risk that it won't be repaid according to its original terms — or at all. When that happens, it's called a default.

The good news is that bond defaults are pretty rare. According to John Nersesian of PIMCO, less than 1.5% of corporate bonds2 issued in the United States default.

U.S. Treasury bonds, historically, are even safer. The U.S. government has yet to default on a treasury bond, bill, or note.

When a bond default does happen, it's usually the result of a high-yield or junk bond with a low rating. High-yield bonds offer a higher interest rate to compensate for their higher risk of default. You can greatly reduce your risk of owning a bond that enters default by checking the credit rating of the bond's issuer.

Most bonds issued in the United States are rated by Moody's, Standard & Poor's, or Fitch.

Moody's uses Aaa through C for its rating system where Aaa is the highest rating and C is the lowest. Moody's also uses 1, 2, and 3 modifiers for Aa through Caa ratings to further indicate the bond's quality.

Fitch uses AAA through D ratings where AAA represents bonds with the lowest risk of default, and D indicates that the bond is in default. Standard & Poor's uses a similar scale.

I'd avoid anything that Fitch or Standard & Poor's has rated BB or lower, or that Moody's has rated Baa3 or lower. High-yield bonds made Michael Milken rich. Most of us non-billionaires do not have the risk tolerance for it.

Instead, look for bonds rated A1/A through Aaa/AAA. Government bonds, whether treasury or municipal, typically fit the bill. So do most corporate and foreign sovereign bonds. Your brokerage's research tools can tell you the current rating of a bond you're considering. Be aware, however, that ratings and risk can change over time.

Interest Rate Risk

Interest rate risk is another risk of bond investing. Interest rates fluctuate over time. Sometimes rates fall. When they do, that's good for you. Your bonds will continue to earn interest income according to its coupon and payment schedule, and its trading value will increase. Should rates rise, however, you're losing the opportunity to earn more from your bond if you continue to hold it.

You can always sell your lower-coupon bond, and use the proceeds to buy a bond with a higher coupon rate. But remember: when interest rates rise, the price of existing, lower-coupon bonds fall. You'll likely lose part of your principal investment. This is known as market risk or price risk.

Market or Price Risk

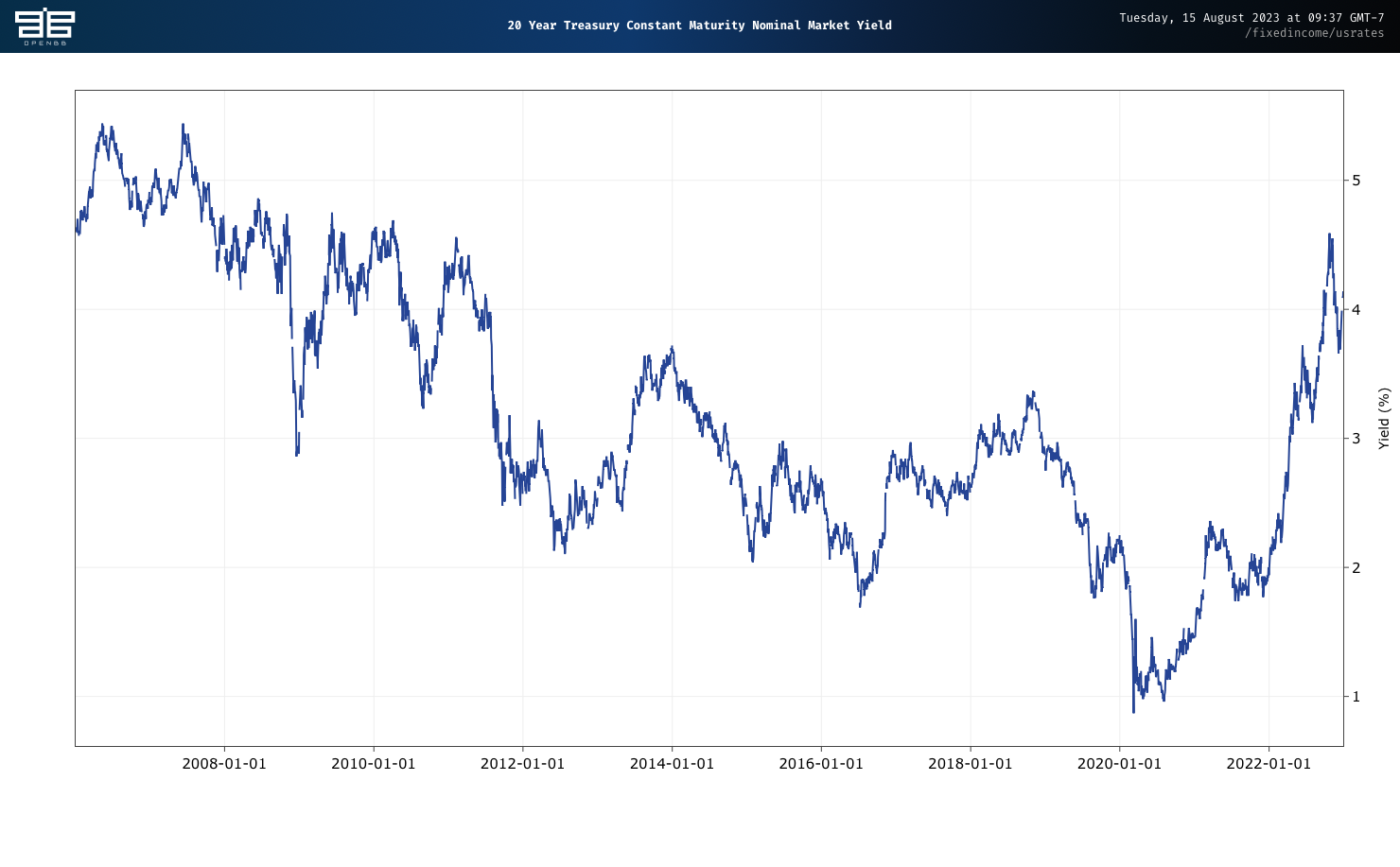

Bond prices and yields change when benchmark interest rates do. Over 10, 20, or 30 years, interest rates may go up or way, way down. The following chart shows the Federal Funds Effective Rate from July 2003 through July of 2023. Rates ranged from a high of 5.26 percent in 2007 to a low of 0.07 percent in December 2011. As of July 2023, the rate was 5.12 percent.

If you purchased a 20-Year treasury bond in 2007, when yields were around 5 percent, you probably saw its resale value increase sharply between 2012 and 2022. Between 2012 and 2022, yields for new issue bonds reached historic lows, ranging from about 1.5 percent to about 3.5 percent.

Consider 912810SN9, a 30-Year treasury bond issued May 15, 2020. Its original coupon was 1.250%, and originally sold at $97.734 per $100. Its current trading value is just shy of $51.30 per $100.

The good news is that a bond's price usually approaches its par value (face value) as the bond approaches maturity. If your strategy is to buy and hold your bonds until they mature, you don't need to worry as much about market risk.

On the other hand, if you do sell your bond at a loss, it's considered a capital loss. You can use capital losses to offset capital gains3, and up to $3,000 in wage income. At least, that's what the pros tell me. Remember that I am not a financial professional.

Call Risk

When prevailing interest rates fall, your bond may be called, or redeemed before it reaches maturity.

When a bond is called, the issuer pays off the bond's principal amount and any interest accrued through the call date. In most cases, the issuer also completes a new bond offering at a lower coupon rate. You miss out on future interest payments, but you get that money back to invest elsewhere.

A bond may be continuously callable, which means that it can be called at any time. Other bonds have a call schedule, or a series of dates on which the issuer can retire the bond.

To avoid call risk entirely, look for bonds that have call protection, and check whether there's a call schedule. Most U.S. Treasury bills, bonds, and notes offer call protection. You'll receive interest payments as scheduled for the term of the bond. Some shoter-term corporate bonds also offer call protection for some or all of their duration. You can research whether a bond has call protection using your brokerage website's tools.

Inflation Risk

Lastly, there's inflation risk, or the risk that your money will have less purchasing power over time. While the stock market typically keeps pace with inflation, bonds may not.

Inflation is hard to predict, though. It's possible to have low levels of inflation for long periods of time, followed by a spike due to one or more global crises. Or an economy can enter an extended period of deflation in which prices fall. Japan famously experienced two decades of deflation and minimal growth.

To guard against inflation's effect on your bond income, invest in Treasury Inflation Protected Securities (TIPS).

Conclusion

Bonds should be part of your portfolio. They reduce the value or price fluctuations of your portfolio (also known as volatility) and provide income when stocks may not. Bonds are particularly good for achieving medium and long-term savings goals where certainty matters.

When it comes to retirement, the rule of thumb is that your bond allocation should be 110 minus your age. Let's assume that you'd like to retire in 2040 at age 64. According to the rule of 110, about 46 percent of your portfolio should be invested in bonds. A quick look at some of 2040 target date funds, however, shows bond allocations of about 15 percent as of 2023. Expect those allocations to change as we get closer to 2040.

As with any form of investment, aim for diversification. At a minimum, that means a mix of corporate, treasury, and municipal bonds, or treasury bonds with different durations and payments that are spread out over a year. You may also wish to add foreign government bonds, particularly ones denominated in U.S. dollars. Diversification helps limit the impact of any losses you may incur.

-

Source: Federal Funds Effective Rate since 1954. ↩

-

Bond Bootcamp: Develop a Deeper Understanding of Fixed Income Investing Nersesian says this about 16 minutes in. ↩

-

Capital gains occur when you sell an asset for more than you paid for it. ↩