An Introduction to IndexedDB

This piece was originally published on dev.opera.com, which no longer exists. Some links and images may be broken. Some formatting may be off. You may republish this post under a CC-BY 3.0 license.

IndexedDB offers a powerful way to store and retrieve data in the browser. As with server-side databases, IndexedDB allows us to generate keys, search data, or sort it by a particular field.

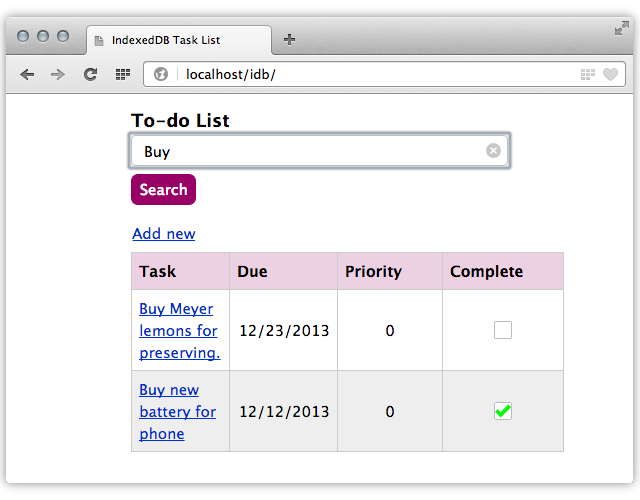

In this article, we’ll dig into the IndexedDB API by building a to-do list manager. But first, let’s look at some of the concepts around databases and IndexedDB.

What is IndexedDB?

IndexedDB is an asynchronous, transactional, key-value object store. That’s a lot of concepts to introduce in one sentence, but I’ll try to explain them.

Asynchronous means that IndexedDB won’t block the user interface. Operations happen “soon” rather than immediately. This allows the user interface to respond to other input. To contrast: localStorage is synchronous. Operations are processed immediately, and nothing else will happen until the operation completes. Large reads and writes can slow your application significantly.

Transactional means that operations in IndexedDB are all-or-nothing. Should an operation fail for some reason, the database will revert to its previous state. You’ll never have a partially-written record with an IndexedDB database.

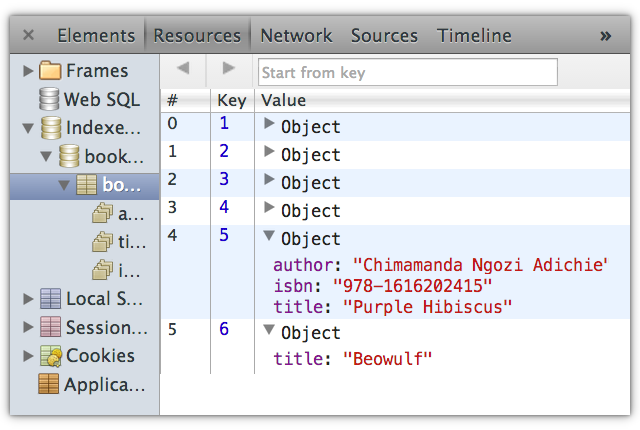

A key-value object store means that each record is an object, as opposed to a row. Traditional databases use a relational model. Data is organized by table, typically with relationships between the values of one table and the keys of another (Figure 1).

In a key-value object store, each record is a self-contained object. It may, but usually doesn’t, have a relationship to records in another object store. Each record may even differ radically from other objects in the same store.

This is the biggest difference between IndexedDB and more traditional databases such as Web SQL or MySQL. With SQL databases, every field must contain a value, even if that value is NULL. With IndexedDB, our schema or database structure can be as flexible as we need it to be.

IndexedDB also has a much larger data capacity than localStorage — no less than 250MB in most browsers. Upper limits vary. In Internet Explorer, 250MB is the cap. Chrome and Opera use a percentage of available space. Firefox has no known limit. We can also use IndexedDB to store binary data in addition to strings. In other words, we get the familiarity of a JavaScript-like syntax with the data consistency and capacity of Web SQL.

Current browser support

Unfortunately, IndexedDB isn’t available in all major browsers yet. Opera 15+, Chrome 24+, Firefox 15+, and Internet Explorer 10+ support it. Older versions of Chrome and Firefox support experimental, vendor-prefixed versions of the API. We won’t cover those here.

Safari doesn’t support IndexedDB at all, nor do Presto-based versions of Opera (≤ 12). Instead they support the older Web SQL specification. IndexedDBShim smooths out most, but not all of these differences. For browsers that support neither, the best alternative is still to use a server-side database.

Testing for IndexedDB support

To test for IndexedDB support, do the following.

var hasIDB = typeof window.indexedDB != 'undefined';

Or use Modernizr.

var hasIDB = Modernizr.indexeddb;

Keep in mind that these tests only work for the latest, un-prefixed version of IndexedDB.

Building a task manager

Only excerpts from the demo project are featured in this article. But you can download the source to get a better sense of how each function works in context.

With our task manager, we’ll want to:

- save tasks;

- set start and due dates;

- set a task’s priority;

- add a note to each task;

- and search task names and notes.

First, let’s create the form that we’ll use to add new tasks to our database.

<form id="addnew">

<div>

<!-- Used for updates -->

<input type="hidden" name="key" id="key" value="">

<label for="task">What do you need to do? (required)</label>

<input type="text" name="task" id="task" value="" required>

</div>

<div class="txtright">

<input type="checkbox" name="status" id="status"><label for="status">Completed?</label>

</div>

<div>

<label for="start">Start date:</label>

<input type="date" id="start" name="start" value="">

</div>

<div>

<label for="due">Due date:</label>

<input type="date" id="due" name="due" value="">

</div>

<div>

<label for="priority">Priority:</label>

<select id="priority" name="priority">

<option value="0">None</option>

<option value="1">1 - High</option>

<option value="2">2</option>

<option value="3">3 - Medium</option>

<option value="4">4</option>

<option value="5">5 - Low</option>

</select>

</div>

<div>

<label for="tasknotes">Task notes</label>

<textarea id="tasknotes" name="tasknotes" cols="30" rows="3"></textarea>

<button type="submit" id="submit">Save entry</button>

<button type="button" id="delete" class="hidden" >Delete entry</button>

</div>

</form>

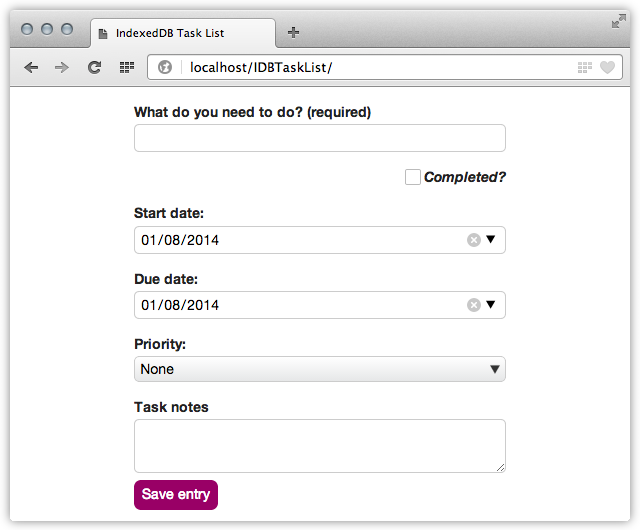

The HTML above (plus some CSS) produces a form that looks a bit like the example in Figure 2.

What do you need to do? is the only required form field, and we’ll use this form to add and update tasks. Now that we’ve defined what we’re collecting, let’s do the work of building our database.

Creating a database

To create an IndexedDB database, use the open() method of the indexedDB object.

var idb = indexedDB.open('IDBTaskManager', 1);

That first argument is the name of our database. It’s required, and must be a string. Database names can be just about any string, including an empty one (''). However, each database name must be unique for its origin. The origin is the combination of scheme, host name, and port — https://dev.opera.com, or http://www.example.com:80, for example.

The optional second argument is the version number of our database. Since this is the first iteration of our application, we’ve set it to 1.

Without a version number argument, open will create the database if it doesn’t exist, and set its version to 1. If the database does exist, open will create a connection to it.

Version numbers must be an integer greater than zero. Float values will just be converted to integers; 2.5 will become 2 and 0.8 will become 0 (which causes an error). The maximum allowed value of a version number is 253 or 9,007,199,254,740,992. This maximum also applies to generated keys.

NOTE: In Opera, you can inspect IndexedDB object stores, keys and values in the Resources panel of Opera’s Developer tools (Developer → Web Inspector).

Should this open operation work, it will return a IDBOpenDBRequest object, and trigger a success event. Let’s define an onsuccess callback for this event. Within it, we will assign the IDBDatabase object event.target.result to a variable that shares scope with our other functions.

var dbobject; // Define a global variable to hold our database object

idb.onsuccess = function(evt){

dbobject = evt.target.result;

}

With IndexedDB, every operation or transaction on our database must occur within a callback function. To do that, our database object needs to be available to every function that makes a transaction.

Database versioning

When the database version of the application is greater than what’s stored by the client, the browser will fire an upgradeneeded event. This includes the application’s first run, when the initial version number is zero.

Triggering an upgradeneeded event is the only way to make structural changes to a database. Structural changes include creating and deleting object stores, or adding indexes. We can make these changes within an onupgradeneeded callback, as shown below.

idb.onupgradeneeded = function (evt) {

if (evt.oldVersion < 1) {

// Create our object store and define indexes.

}

}

Attempting to create an object store or index that already exists will cause an error. But we can use the oldVersion property of the upgradeneeded event to manage changes, as we’ll see elsewhere in this piece.

If fired, the upgradeneeded event will occur before the connection success event. Our dbobject variable won’t be defined when idb.onupgradeneeded is called. Keep that in mind when developing applications.

Creating an object store

Creating a database alone is pointless. To save and manipulate records, we’ll also need to create an object store. Object stores are similar to SQL tables; it’s the unit that holds our collection of entries or records.

Adding an object store is a structural change, so we’ll need to do it from within our onupgradeneeded callback. Let’s add an object store named tasks using the createObjectStore method.

idb.onupgradeneeded = function(evt){

var dbobject = evt.target.result;

// Check our version number

if (evt.oldVersion < 1) {

dbobject.createObjectStore('tasks',{autoIncrement: true});

}

};

The first argument for createObjectStore is required. It’s the name of the object store. The second argument is optional, but must be a dictionary that defines key options for the store.

Dictionaries resemble JavaScript object literals. But they’re actually associative arrays with defined keys and values. Dictionaries let us pass arguments without worrying about their order. With createObjectStore, the dictionary may only contain the following properties and values.

keyPath: Defines which object property should be used as the key for each record;nullby default.autoIncrement: A boolean value that determines whether or not to auto-generate keys for each record;falseby default.

Setting a keyPath makes the specified property a required one. Using {keyPath: 'task'}, for example, means that every object added to the store must have a task property.

In our demo, however, we’ll use autoIncrement. Using either autoIncrement or keyPath means that we won’t have to specify a key argument for the add and put methods.

NOTE: You can use autoIncrement and keyPath together. Keys will be numeric and generated. Objects will have a required field.

Working with records

Working with records — adding, updating, deleting, or retrieving — is generally a four-step process.

- Create a transaction connection to one or more object stores using

readwriteorreadonlymode. -

Specify which object store to query with our transaction request.

-

Make a request using the one of the request methods, or a cursor object.

-

Do something with the results, if any, using an

onsuccesscallback. Working with individual records is slightly different than working with sets of records. In this section we’ll work with single records. In the section Using cursors to retrieve multiple records, we’ll work with sets.

Adding a record

To add a record, we have two options: add() and put(). The add() method can only be used when adding a new record, while put() can be used to add or update records. Both of these methods accept up to two arguments.

value(required): The object to savekey(optional): The object’s key; only necessary ifautoIncrementis false, and nokeyPathis defined.

Let’s save a task to our database when the user submits the task form.

var addnewhandler, addnew;

addnew = document.getElementById('addnew');

addnewhandler = function (evt) {

'use strict';

evt.preventDefault();

var entry = {}, transaction, objectstore, request, fields = evt.target, o;

// Build our task object.

for (o in fields) {

if ( fields.hasOwnProperty(o)) {

entry[o] = fields[o].value;

}

}

// Open a transaction for writing

transaction = dbobject.transaction(['tasks'], 'readwrite');

objectstore = transaction.objectStore('tasks');

// Save the entry object

request = objectstore.add(entry);

transaction.oncomplete = function (evt) {

displaytasks(dbobject);

};

transaction.onerror = errorhandler; };

addnew.addEventListener('submit', addnewhandler);

We don’t really need to sanitize these values, since harmful input is limited to the client. Do escape < and > characters when outputting so they aren’t mistaken for HTML tag boundaries. If you plan to synchronize IndexedDB data with a database server, however, be sure to filter and escape user input as appropriate for your database.

Our next step: open a transaction connection to the database object using the transaction method. The transaction method accepts two arguments: a sequence of object store names, and the mode of this transaction.

A sequence is a list of one or more object stores on which to perform transactions. Here, we are only opening one object store, tasks.

But let’s say that our application allows us to assign tasks to people. Those people and their roles are in the object store assignees. If we also wanted to use read or write from assignees, we could open both at once.

transaction = dbobject.transaction(['tasks', 'assignees'], 'readwrite');

NOTE: In the latest versions of most browsers, the [ and ] are optional if you’re opening a connection to a single object store. Some slightly older browsers still require them. For broadest compatibility, use square brackets.

For the mode argument, we have two choices: readwrite and readonly. Using readwrite lets us retrieve, add, update, or delete records. However, to preserve data integrity, only one readwrite transaction can run at a time.

Use readonly when if you only want to retrieve records for display. Multiple readonly can run on the same object store at the same time, which helps performance. Since we are adding a record, we’ll use readwrite mode.

Step three is to select which object store to use for our request using transaction.objectStore('tasks');.

Finally, request = objectstore.add(entry) writes our entry object to the database. The displaytasks function will be invoked when the transaction completes.

To add multiple records, just invoke the add() method multiple times using the same request object.

request = objectstore.add({object1:'Test object 1'});

request = objectstore.add({object2:'Test object 2'});

request = objectstore.add({object3:'Test object 3'});

In this case, the success and complete events will fire once after all add or put operations complete, instead of firing once for each.

Updating a record

Updates must use the put method, and must include a key argument. Leaving it out will create a new record, but that’s not what we want here.

Our application uses the same view for both adding and editing tasks. Let’s use the addnewhandler function to handle additions and updates. We just need to modify it for updates by adding a conditional. If our form’s key field is empty, we’ll add a record. If it has a value, we will update with put.

addnewhandler = function (evt) {

evt.preventDefault();

var entry = {}, transaction, objectstore, request, fields = evt.target, o;

for (o in fields) {

if ( fields.hasOwnProperty(o)) {

entry[o] = fields[o].value;

}

}

transaction = dbobject.transaction(['tasks'], 'readwrite');

objectstore = transaction.objectStore('tasks');

// Save the entry object with a key if one is available.

if(fields.key.value){

// +fields.key.value converts our key to a number

request = objectstore.put(entry, +fields.key.value);

} else {

request = objectstore.add(entry);

}

transaction.oncomplete = function (evt) {

displaytasks(dbobject);

};

transaction.onerror = errorhandler;

};

Retrieving a record

In order to update a record, of course, we first need to retrieve it. Here we can use the get method. When the user clicks on a task in the list, it will trigger a hashchange event. Let’s define a hashchangehandler function to retrieve matching item.

hashchangehandler = function (evt) {

var transaction, objectstore, request, key;

if (window.location.hash) {

// Extract digit characters from the hash, and convert to a number.

// Generated IndexedDB keys are numbers. String values won’t work.

key = +window.location.hash.match(/\d/g).join('');

// Run a read-only transaction on this object store.

transaction = dbobject.transaction(['tasks'], 'readonly');

objectstore = transaction.objectStore('tasks');

// Retrieve the record by its key

request = objectstore.get(key);

// If it’s successful, update our form fields.

request.onsuccess = function (successevent) {

var o, data = successevent.target.result;

for(o in data) {

if( o == 'status') {

addnew.status.checked = !!data.status;

}

addnew[o] = data[o];

}

};

transaction.oncomplete = function (evt) {

hide('#tasklist');

show('#addnew');

}

}

};

The get method retrieves our record. It accepts a single argument: the key of the record to retrieve. Since we’re just retrieving a record our transaction mode can be readonly.

NOTE: IndexedDB keys are strict about type, and our generated keys are numbers. Passing a string to get — even if numeric — won’t work. You’ll need to convert the argument to a number as we’ve done above.

If our request is successful, we will populate the #addnew form with the result of our get transaction.

You should define an onsuccess callback any time your request may return results. We’ve also defined an oncomplete callback that will be invoked when the transaction completes rather than when the request ends. A transaction will always finish even if a request fails.

Deleting a record

Let’s use a similar approach for deleting a record as we did for retrieving one. This time, however, we’ll use the delete method. Like get, delete requires a single argument, the key of the object to delete from the store. We also need to open our transaction in readwrite mode.

deletehandler = function (evt) {

var transaction, objectstore, request, key;

if (window.location.hash) {

// Retrieve the key from the hash and convert it to a number

key = +window.location.hash.match(/\d/g).join('');

// Perform the transaction

transaction = dbobject.transaction(['tasks'], 'readwrite');

objectstore = transaction.objectStore('tasks');

request = objectstore.delete(key);

// Recreate the task list display

transaction.oncomplete = function (evt) {

tbody.innerHTML = '';

displaytasks(dbobject);

};

transaction.onerror = errorhandler;

}

};

Here we’ve only defined an oncomplete handler for the transaction object, since delete won’t return a result set.

Record deletions and auto-generated keys

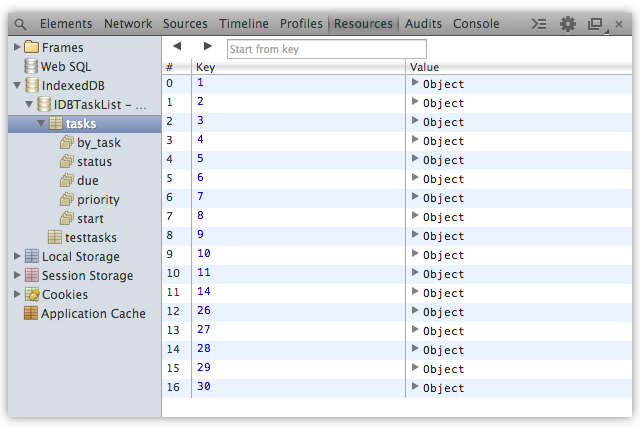

As with other kinds of databases, deleting a record does not reset the value of the key generator. In Figure 3, you can see that we have only 16 records in our database. However, the most recent entry has a key of 30.

It’s possible, however, to reuse the key of a deleted record. Just pass the desired key as the second argument of add or put.

Using cursors to retrieve multiple records

Retrieving sets of records works a bit differently. For that, we need to use a cursor. Cursors are, as explained by the IndexedDB specification, are a transient mechanism used to iterate over multiple records in a database. In a range of records, the cursor keeps track of where it is in the sequence. The cursor moves in ascending or descending order, depending on which direction chosen when opening the cursor. Cursors are a little bit like using a while loop.

Let’s take a look at how to retrieve a set of results with a cursor.

var displaytasks = function (database) {

var transaction, objectstore, request;

transaction = dbobject.transaction(['tasks'], 'readonly');

objectstore = transaction.objectStore('tasks');

request = objectstore.openCursor(IDBKeyRange.lowerBound(0), 'next');

request.onsuccess = function (successevent) {

var task, tbody = document.querySelector('#list tbody');

if (request.result) {

task = buildtask(request.result);

tbody.appendChild(task);

cursor.continue(); // advance to the next result

}

}

}

Again we’ve started by creating a transaction object and selecting an object store. What we’ve done differently however, is open a cursor object using the openCursor method.

The openCursor method accepts up to two arguments. Both are optional.

- range: Must be either a key or a key range; and

- direction: Must be one of

'next','prev','nextunique', or'prevunique'.

Creating a key range

To create a key range, we need to use the IDBKeyRange interface. All of its methods are static.

IDBKeyRange.lowerBound: Sets a lower key boundary only.IDBKeyRange.upperbound: Sets an upper key boundary only.IDBKeyRange.bound: Sets upper and lower key boundaries.IDBKeyRange.only: Accepts a single key value; a cursor-based alternative toget.

We’ve set a lower bound of zero here using IDBKeyRange.lowerBound, and haven’t set an upper limit. Every record with a key value that’s greater than zero will be returned — that’s every record in the tasks object store, oldest first.

IDBKeyRange.upperBound retrieves all objects with key values that are less than the argument provided. For example, IDBKeyRange.upperBound(20) would return every object with a key of 20 or less.

IDBKeyRange.bound retrieves objects with key values ranging from the lower bound argument through the upper bound argument. To retrieve records with keys between 11 and 20, for example, we would use IDBKeyRange.bound(11,20).

None of these methods return a number of results. Instead they return keys within the range. Let’s say, for example, that our object store keys are 1, 2, 4, 8, 9, 11, 15, 16, 20, 21, 22, and 23. We’ve deleted a few entries, so there are gaps in our key sequence.

IDBKeyRange.lowerBound(0)would return all objects.IDBKeyRange.lowerBound(10)would return objects for keys 11, 15, 16, 20, 21, 22 ,and 23.IDBKeyRange.upperBound(0)wouldn’t return any objects.IDBKeyRange.upperBound(10)wouldn’t return objects for keys 1, 2, 4, 8, and 9.IDBKeyRange.bound(0,20)would return all objects except for keys 21, 22, and 23.

Though the bounds of a key range are included in the result set, it’s possible to exclude them with an additional open argument. It must be a boolean, and false is the default. To skip the first record in our result set, for instance, we could use IDBKeyRange.lowerBound(0, true).

IDBKeyRange.bound is a little different. It accepts two additional arguments: lowerOpen and upperOpen. If we wanted to exclude our first and last results from an IDBKeyRange.bound range, we would pass true twice: IDBKeyRange.bound(0, 10, true, true).

Selecting a cursor direction

The second argument of openCursor indicates which direction the cursor should move. Using next means that our records will be sorted by key in ascending order. Using prev — short for “previous” — orders results in descending order. We can also exclude duplicate keys with nextunique and prevunique, which is particularly useful when working with indexed properties.

Adding indexes

So far, we’ve retrieved entries by key and key range. But for a to-do list, we may want to retrieve and sort our records by task name, priority, due date, or status. This is where indexes come in handy.

NOTE: As of publication, IndexedDBShim, does not fully support opening cursors on indexes. You’ll need to implement another sorting mechanism.

Think of indexes as a quick way to sort and order your records. Indexes lets you look up objects by their properties rather than by their keys.

To add an index to our object store, we need to use the createIndex method. Because adding an index is a structural change, we’ll need to do it in response to a versionchange event using an onupgradeneeded callback. Let’s update our onupgradeneeded function from above.

idb.onupgradeneeded = function (evt) {

var tasks, transaction;

dbobject = evt.target.result;

if (evt.oldVersion < 1) {

tasks = dbobject.createObjectStore('tasks', {autoIncrement: true});

// Create indexes on the object store.

transaction = evt.target.transaction.objectStore('tasks');

transaction.createIndex('by_task', 'task');

transaction.createIndex('priority', 'priority');

transaction.createIndex('status', 'status');

transaction.createIndex('due', 'due');

transaction.createIndex('start', 'start');

}

};

The createIndex method accepts up to three arguments.

name(required): The name of the index to add.keyPath(required): The object property to track.optionalParameters: A dictionary containing settings —uniqueand/ormultiEntry— for the index.

Here we’ve added indexes to our task, priority, status, start, due and fields. Indexes may share the same name as the properties they track.

Only those objects containing the indexed property will be entered in the index store.

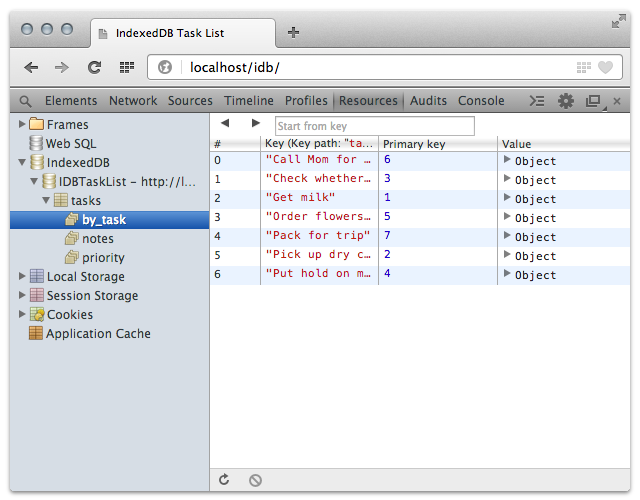

by_task index table in OperaWhen the properties of a record change, those changes are also reflected in the index table. Let’s take a look at retrieving records based on an index. We’ll update our displaytasks function from above.

Retrieving records using an index

In the previous version of our displaytasks function, we opened a cursor on our object store. Here we’ll need to add a line that retrieves our by_task index instead. Then we’ll call openCursor on the index.

var displaytasks = function (database) {

var transaction, objectstore, request, index;

transaction = dbobject.transaction(['tasks'], 'readonly');

objectstore = transaction.objectStore('tasks');

// New line to select the index

index = objectstore.index('by_task');

// Our request opens a cursor on the index,

// rather than the object store.

request = index.openCursor(IDBKeyRange.lowerBound(0), 'next');

request.onsuccess = function (successevent) {

var task, tbody = document.querySelector('#list tbody');

if (request.result) {

task = buildtask(request.result);

tbody.appendChild(task);

cursor.continue();

}

}

}

Indexes also order values for each property tracked. Our updated displaytasks function above will return an alphabetical list of tasks.

Limits of indexes

Unfortunately, IndexedDB lacks the kind of full-text searching that you would find with SQL databases such as MySQL or PostgreSQL. Instead, we need to filter our results using a regular expression. Let’s look at an example using our search form. When it’s submitted, we’ll grab the form value and use it to create a regular expression. Then we’ll test each task for a match.

var searchhandler, search = document.getElementById('search');

searchhandler = function (evt) {

evt.preventDefault();

var transaction, objectstore, index, request;

transaction = dbobject.transaction(['tasks'], 'readwrite');

objectstore = transaction.objectStore('tasks');

index = objectstore.index('by_task');

request = index.openCursor(IDBKeyRange.lowerBound(0), 'next');

request.onsuccess = function (successevent) {

var reg, cursor, task;

reg = new RegExp(evt.target.find.value, "i");

cursor = request.result;

if (cursor !== null) {

if (reg.test(cursor.value.task)) {

task = buildtask(cursor);

}

cursor.continue();

}

}

}

search.addEventListener('submit', searchhandler);

Figure 6 shows the results of such a search.

Regular expression searches have their limits, however. A search for “cafe” won’t match “café” since “e” and “é” are two different characters. However, using this technique means you can pass a regular expression as an argument and search for caf.*

Conclusion

IndexedDB brings basic database capability to the browser, making it possible to build web applications that work online and off. It does, however, require shifting your mind a bit, and becoming familiar with database concepts. To learn all of the ins and outs of IndexedDB, read through the IndexedDB specification. It’s not an easy read, but it is the definitive reference. Mozilla Developer Network also covers some of the concepts behind IndexedDB, in case they’re unclear.